[wonderplugin_gridgallery id=4]

2018 Conservation Camp Picture Gallery

[wonderplugin_gridgallery id=3]

PENNSYLVANIA GAME COMMISSION RUFFED GROUSE FILM WINS BIG

Between 2001 and 2005, the ruffed grouse population suffered a 63 percent decline in Pennsylvania. No one was sure why but in 2015 through 2016, Game Commission biologist Lisa Williams and her team confirmed their suspicions about Pennsylvania’s state bird being affected by the West Nile Virus (WNV).

Grouse chicks were hatched from eggs gathered in the wild, and then inoculated with WNV. Within the first week 40 percent of the chicks died. After two weeks, an additional 40 percent of the chicks showed so much organ damage that they probably could not have survived in their natural environment.

After the challenge study was completed, the laboratory findings were then tested on wild grouse in Pennsylvania by looking for WNV-positive antibodies in harvested grouse. This testing is the first of its kind where lab results were then tested in wild populations.

Williams rallied hundreds of hunters across the state to send in blood samples when they harvested a grouse during the hunting season. Game Commission pathologist Justin Brown and their research partners at Colorado State University and the University of Guelph then did the careful lab work to assess WNV exposure in wild grouse. By incorporating these findings into habitat management planning, the Game Commission and partners hope to direct habitat management efforts to areas where grouse populations have the best chance of responding.

Williams’ research then caught the ear of one of the Game Commission staff filmmakers.

Game Commission filmmaker Tracy Graziano, armed with her Canon C500 and Final Cut X editing program, set out to tell Williams’ story that continues to unfold even today. Graziano completed the 9-minute documentary in late January 2017 after 18 months of shooting and countless hours in the field. She has been with the agency for eight years but has been creating science and wildlife documentaries since 1999.

“The most rewarding thing I can hope for in any of my film projects is to help influence change for the benefit of wildlife and conservation,” said Graziano.

“With more than 27,000 YouTube views to date, I believe the ‘Ruffed Grouse’ film was critically important in raising awareness among hunters about the risk of WNV to grouse and is one of the reasons other state wildlife agencies started looking into WNV as a contributing cause of decreasing grouse populations,” Lisa Williams said.

Game Commission Executive Director Bryan Burhans concurs.

“Lisa Williams’ research into the ruffed grouse population decline in Pennsylvania is cutting-edge science-based wildlife management,” Burhans said. “Documenting these important findings by using the latest technology by skilled filmmaker Tracy Graziano so others can learn and benefit exemplifies why the Pennsylvania Game Commission is at the forefront in modern wildlife management.”

“Ruffed Grouse” won awards from the following:

- The University of Idaho Fish & Wildlife Film Festival 2017, Idaho, “Natural History Documentary-Short” category

- American Conservation Film Festival 2017, West Virginia, Official Selection “Conservation Film Short” category

- Wildlife Conservation Film Festival 2017, New York, Official Selection “Wildlife Conservation” category

- FIIN 2017, Portugal, Official Selection “Films of Nature” category

- NatureTrack Film Festival 2018, California, Official Selection “Conservation” category

- Outdoor Film Festival 2018, Utah, Official Selection “Categories by Species”

This past July, the “Ruffed Grouse” film was recognized with its most recent award at the Association for Conservation Information (ACI) conference in Springfield, Missouri. The film took third place in the 2018 “Video Long” category.

ACI is a professional organization that recognizes excellence in educational work completed by state and federal fish and wildlife agencies across North America.

CWD RULES AFFECT OUT OF STATE HUNTERS

HARRISBURG, PA – Pennsylvanians who harvest deer, elk, mule deer or moose out-of-state likely can’t bring them home without first removing the carcass parts with the highest risk of transmitting chronic wasting disease (CWD).

Pennsylvania long has prohibited the importation of high-risk cervid parts from areas where CWD has been detected. This prohibition reduces the possibility of CWD, which always is fatal to the cervids it infects, spreading to new areas within Pennsylvania.

Earlier this year, the Game Commission strengthened its ban on importing high-risk cervid parts by prohibiting any deer harvested in New York, Ohio, Maryland or West Virginia from being brought back to Pennsylvania whole.

In previous hunting seasons, the prohibition applied only to deer harvested within counties in those states where CWD has been detected.

With the change, Pennsylvanians who harvest deer anywhere in New York, Ohio, Maryland or West Virginia either must have them processed in those states or remove the high-risk parts before bringing the meat and other low-risk parts back into Pennsylvania.

There now are 24 states and two Canadian provinces from which high-risk cervid parts cannot be imported into Pennsylvania.

The parts ban affects hunters who harvest deer, elk, moose, mule deer and other cervids in: Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming; as well as the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

High-risk parts include: the head (including brain, tonsils, eyes and any lymph nodes); spinal cord/backbone; spleen; skull plate with attached antlers, if visible brain or spinal cord tissue is present; cape, if visible brain or spinal cord tissue is present; upper canine teeth, if root structure or other soft tissue is present; any object or article containing visible brain or spinal cord tissue; unfinished taxidermy mounts; and brain-tanned hides.

Hunters who are successful in those states and provinces from which the importation of high-risk parts into Pennsylvania is banned are allowed to import meat from any deer, elk, moose, mule deer or caribou, so long as the backbone is not present.

Successful hunters also are allowed to bring back cleaned skull plates with attached antlers, if no visible brain or spinal cord tissue is present; tanned hide or raw hide with no visible brain or spinal cord tissue present; capes, if no visible brain or spinal cord tissue is present; upper canine teeth, if no root structure or other soft tissue is present; and finished taxidermy mounts.

Hunters who harvest cervids in a state or province where CWD is known to exist also should follow instructions from that state’s wildlife agency on how and where to submit the appropriate samples to have their animal tested. If, after returning to Pennsylvania, a hunter is notified that his or her harvest tested positive for CWD, the hunter is encouraged to immediately contact the Game Commission region office that serves the county in which they reside for disposal recommendations and assistance.

A list of region offices and contact information can be found at www.pgc.pa.gov by scrolling to the bottom of any page to select the “Connect with Us” tab.

Pennsylvania first detected chronic wasting disease in 2012 at a captive deer facility in Adams County. The disease has since been detected in free-ranging and captive deer in a few, isolated areas of Pennsylvania.

Presently, there are three active Disease Management Areas (DMAs) within Pennsylvania where special regulations apply to help prevent CWD from spreading to new areas. Deer harvested within DMAs also cannot be transported whole to points outside the DMA.

Much more information on CWD and Pennsylvania’s DMAs is available at www.pgc.pa.gov.

MEDIA CONTACT: Travis Lau – 717-705-6541

Courtesy PA Game Commission

Chronic Wasting Disease in Pennsylvania Webinar October 4th

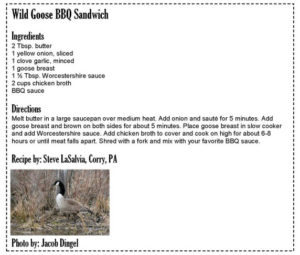

Wild Goose BBQ Sandwich

It’s Wild Game Wednesday!

Raise your hand if you’ve ever felt a special sense of pride when preparing a meal that included fresh, wild game. There is just something satisfying about knowing exactly where your meat came from that makes wild game meals even more appealing – and – appetizing! Oftentimes, there is an exciting story to accompany the game that’s been prepared. Delicious food paired with great conversation, what more could you ask for?

On Wild Game Wednesday, we take a moment to recognize one of the most important reasons people take to the woods and fields to hunt: to fill their freezers with types of fresh, organic meat. These weekly posts include delicious, easy and in-season wild game recipes from the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Game Cookbook that you and your family can prepare.

For all our goose hunters out there, this one is for you! Let us know if you try this recipe.

If you are interested in more wild game recipes submitted by people from around Pennsylvania, visit www.theoutdoorshop.state.pa.us/FBG/ to purchase the second edition of the cookbook for less than $10!

Courtesy PA Game Commission

View The Live Elk Cam

We realize not everyone will be able to visit Benezette this fall, but we still want you to have the elk-viewing opportunity. The live elk cam streaming on our website lets you be able to watch for elk from the comfort of your own home! WATCH IT LIVE HERE. We’ve had a very active elk cam season so far this season, so be sure to check it out. The best times to view are at dawn and dusk. You may also see white-tailed deer, turkeys and groundhogs. This stream is the product of the coordinated efforts of the Pennsylvania Game Commission, HDonTap and the North Central Pennsylvania Regional Planning and Development Commission.

CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT ELK IN PENNSYLVANIA.

Courtesy PA Game Commission

We Need Your Help To Keep Bald Eagles Alive

Did you know that hunters are responsible for the return of the bald eagle in our state? In the late 1970’s there were only TWO or THREE bald eagle nests in our whole state. Today, with the success of the Game Commission’s recovery program, we proudly have more than 300 nests here at home!

Unfortunately, we have recently lost a number of bald eagles here due to lead poisoning. We need our hunters help to keep our eagles alive. Lead is an easy metal to use for a variety of purposes. As a result, humans leave behind a lot of lead when interacting with their environment. But lead in the environment is dangerous to eagles and can be fatal if levels within their bodies become high enough.

To help do our part to keep the eagles safe, we are sharing a few suggestions for our hunters. Together, we can help keep our eagles from being an unintended target in the field.

The easiest way to keep our eagles safe is to use a non-lead ammunition when hunting small game. However, we do understand that a lot of hunters still prefer lead ammunition. If you do use it, we kindly ask that you bury any leftover carcasses or cover any gut piles with sticks. This will, at least, detract eagles from ingesting any lead fragments.

Lead that causes toxicity in bald eagles is acquired through ingestion. Research shows that most lead acquisition comes from unretrieved carcasses – gut piles, varmint carcasses left in the field and carcasses of game that couldn’t be located. Bald eagles ingest lead ammunition fragments distributed in the tissues of these carcasses. When the lead hits the bird’s acidic stomach, it gets broken down and absorbed into their bloodstream where it can be distributed to tissues throughout their body.

Lead can affect bodily function, the nervous system, muscular-skeletal and digestive systems and the function of the brain, liver and kidneys. Birds with lead poisoning may be weak, emaciated and uncoordinated. They may not be able to move, fly or walk. They may have seizures, refuse to eat and appear blind. Bald eagles with lead poisoning often do not respond at all when approached.

The bald eagle is proudly lauded as our national emblem. It symbolizes great strength and dignity. Anyone who has ever witnessed a bald eagle flying overhead can tell you how exciting it is to witness one in the wild. We want memories like that to continue to generations to come. As conservationists, and people who love wildlife, we know we join you in wanting to preserve these special birds. We thank you in advance for your assistance.

Click here to learn more about bald eagles in Pennsylvania

Courtesy PA Game Commission

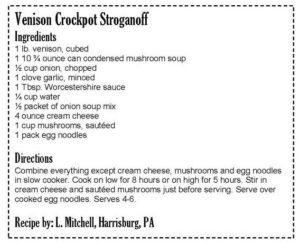

Venison Crockpot Stroganoff

It’s Wild Game Wednesday!

Do you have extra venison in the freezer you’ve been meaning to use? Archery season opens statewide this weekend, Sept. 29, so if you’re looking to cook the meat before this year’s deer season, this recipe might be perfect for you!

On Wild Game Wednesday, we take a moment to recognize one of the most important reasons people take to the woods and fields to hunt: to fill their freezers with types of fresh, organic meat.

These weekly posts include delicious, easy and in-season wild game recipes from the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Game Cookbook that you and your family can prepare.

Let us know if you try this recipe. Enjoy!

If you are interested in more wild game recipes submitted by people from around Pennsylvania, visit www.theoutdoorshop.state.pa.us//FBG/game/GameProductSelect.asp?catid=BKS to purchase the second edition of the cookbook for less than $10!

Courtesy PA Game Commission

What is DMA?

Because we know there are a lot of acronyms posted on the Internet, we want to take a moment to explain some of our most important ones.

Chronic wasting disease, also commonly known as CWD, infects deer, elk and moose, specifically their brain and nervous system, eventually resulting in their death. It can be passed from one animal to another by direct contact, or indirectly when a healthy animal comes in contact with the prion that causes CWD, which is shed by infected animals.

When CWD is detected in a new area, the Game Commission responds by designating a Disease Management Area, or DMA, within which special rules apply regarding the hunting and feeding of deer.

As new cases emerge near a DMA boundary, those DMAs are expanded to encompass larger areas.

CWD first appeared in Pennsylvania in 2012, when it was detected in deer at a captive facility in Adams County, then a few months later, in free-ranging deer in Blair and Bedford counties. Since then, it has been detected in dozens more captive and free-ranging deer. The disease itself was first identified in 1967.

Since last year at this time, DMA 4 has been formed, spanning parts of Lancaster, Lebanon and Berks counties. Meanwhile, DMA 2 and DMA 3 have both been expanded.

DMA 2 now totals more than 4,614 square miles and includes parts of Juniata, Mifflin and Perry counties, in addition to all or parts of Adams, Bedford, Blair, Cambria, Clearfield, Cumberland, Franklin, Fulton, Huntingdon and Somerset counties.

DMA 3 has been expanded to more than 916 square miles. It now includes parts of Armstrong, Cambria and Clarion counties, as well as parts of Clearfield, Indiana and Jefferson counties. Maps and turn-by-turn descriptions of DMA boundaries can be found on the CWD page at the Game Commission’s website.

CLICK HERE FOR AN INTERACTIVE MAP OF PENNSYLVANIA’S DMAS.

With archery season right around the corner, the Game Commission is taking part in several informational events across the three DMAs where the disease has been detected and special rules are in place to help the public better understand CWD and what it means for Pennsylvania’s deer and deer hunting.

DMAs serve to limit CWD’s spread. Hunters who harvest deer within a DMA are prohibited from transporting the deer outside the DMA unless they first remove the carcass parts with the highest risk of transmitting CWD. The meat, the hide and antlers attached to a clean skull plate may be removed from a DMA.

High-risk parts include the head (including brain, tonsils, eyes and lymph nodes); spinal cord and backbone (vertebrae); spleen; skull plate with attached antlers, if visible brain or spinal cord material is present; cape, if visible brain or spinal cord material is present; upper canine teeth, if root structure or other soft material is present; any object or article containing visible brain or spinal cord material; and brain-tanned hide. The use or field possession of urine-based cervid attractants, and the feeding of deer also are prohibited within DMAs.

Hunters who harvest a deer within one of Pennsylvania’s three DMAs can deposit the head of their deer into any CWD Collection Container, pictured below, for free testing and for biological surveillance purposes. The harvest tag must be filled out completely, legibly and physically attached to the deer’s ear. The head must be placed in a plastic garbage bag and sealed before being placed in the collection bin. Hunters will be notified of test results. Skulls and antlers will not be returned.

To date, there have been no reported cases of CWD infection in people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But the disease is always fatal to the cervids it infects As a precaution, CDC recommends people avoid eating meat from deer and elk that look sick or that test positive for CDW.

Currently, there is no practical way to test live animals for CWD, nor is there a vaccine. Clinical signs of CWD include poor posture, lowered head and ears, uncoordinated movement, rough-hair coat, weight loss, increased thirst, excessive drooling, and, ultimately, death.

If you have questions about CWD or a DMA, contact your region office

Courtesy PA Game Commission

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- …

- 29

- Next Page »